Industrial facilities are increasingly called upon to consider the use of wet electrostatic precipitators (WESPs) for emissions control as regulations for PM 2.5 and specific heavy metals become more stringent. Facility and Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) Managers may need to become familiar with WESP technology and how they can be applied to their facilities.

WESPs date back to the 1970’s and are a tried-and-true method for removing submicron particulates, aerosols, SO3, opacity, and condensed heavy metals. They are generally robust and suitable for 24/7 continuous operations. Their use is found in steel melting furnaces, secondary lead smelters, hazardous waste combustors (HWC), medical waste and sewage sludge incinerators, wood products and pellet manufacturing, mineral wool and glass manufacturing, silicon monomer manufacturing, semiconductor manufacturing, and even industrial fryers.

The adjacent figure illustrates WESP’s primary use. The graph shows removal efficiency on the vertical axis and particle size on the horizontal axis. The red curve shows typical WESP performance. The dotted blue curve shows typical Venturi scrubber performance. A comparison shows that a Venturi scrubber is highly effective at removing particles greater than 1 micron in size. However, performance drops off rapidly for particles below 1 micron. WESP performance is relatively immune to particle size and maintains high performance for particles below 1 micron. This capability is derived from the use of electrical forces for particle removal compared to a Venturi scrubber which uses mechanical forces. WESP’s are generally higher capital cost than Venturi scrubbers but lower operating cost. They are used in cases where performance cannot be achieved with a Venturi scrubber or other, lower cost control device.

The adjacent figure illustrates WESP’s primary use. The graph shows removal efficiency on the vertical axis and particle size on the horizontal axis. The red curve shows typical WESP performance. The dotted blue curve shows typical Venturi scrubber performance. A comparison shows that a Venturi scrubber is highly effective at removing particles greater than 1 micron in size. However, performance drops off rapidly for particles below 1 micron. WESP performance is relatively immune to particle size and maintains high performance for particles below 1 micron. This capability is derived from the use of electrical forces for particle removal compared to a Venturi scrubber which uses mechanical forces. WESP’s are generally higher capital cost than Venturi scrubbers but lower operating cost. They are used in cases where performance cannot be achieved with a Venturi scrubber or other, lower cost control device.

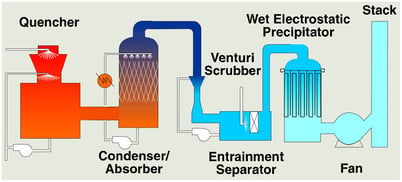

WESPs are often integrated with other control technologies and used as a polishing device at the end of a process. This is shown in the adjacent illustration for a typical waste incinerator. Perhaps the most important aspect to understand about WESP technology is the relationship between performance, size, and cost. Higher performance requires more collection area, larger footprint, and more cost. This is different than other control technologies like a Venturi scrubber or packed bed scrubber. For these devices, size and cost is primarily determined by the gas flow rate while operating cost is determined by performance. Size and cost for a WESP on the other hand is determined not only by gas flow rate but also removal efficiency. It is therefore important to have a good understanding of the range of inlet particulate concentrations and outlet emission limits. Specifying performance of 90%, 95%, or 99% removal will make a substantial difference on size and cost.

WESPs are often integrated with other control technologies and used as a polishing device at the end of a process. This is shown in the adjacent illustration for a typical waste incinerator. Perhaps the most important aspect to understand about WESP technology is the relationship between performance, size, and cost. Higher performance requires more collection area, larger footprint, and more cost. This is different than other control technologies like a Venturi scrubber or packed bed scrubber. For these devices, size and cost is primarily determined by the gas flow rate while operating cost is determined by performance. Size and cost for a WESP on the other hand is determined not only by gas flow rate but also removal efficiency. It is therefore important to have a good understanding of the range of inlet particulate concentrations and outlet emission limits. Specifying performance of 90%, 95%, or 99% removal will make a substantial difference on size and cost.

WESP technologies can vary greatly between vendors which can have an impact on footprint, maintenance, and long-term performance. Some of these differences include:

- Tube geometry (square, round, or hexagonal)

- Tube size

- Tube length

- Operating voltage

- Electrode construction

- Electrode alignment mechanism

- Bottom support grid requirement

- Gas distribution mechanism

It’s recommended that facilities evaluating WESP technologies dedicate time to understand differences in WESP designs and potential impacts on operations. Evaluation may also include how the WESP is integrated with other upstream equipment needed to meet multipollutant emissions criteria.

WESP technology is a substantial investment for any facility but may be the best available control technology for a submicron particulate application.

Click on the link below to download WESP scrubber literature.

Waste oil is recycled and refined into low sulfur marine diesel and other industrial fuels at West Coast refineries. Waste gas is sent to thermal oxidizers for volatile organic compound (VOC) destruction. Sulfur compounds in the waste gas are oxidized to SO2 and removed by a packed bed scrubber. A fraction of SO2 converts to sulfur trioxide (SO3) before entering the scrubber. SO3 further converts to sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and generates a submicron liquid mist upon quenching the gas. New ground level pollutant regulations require removal of sulfuric acid mist before exhausting the flue gas to atmosphere. A multi-pollutant solution is needed to remove both SO2 and sulfuric acid mist.

Waste oil is recycled and refined into low sulfur marine diesel and other industrial fuels at West Coast refineries. Waste gas is sent to thermal oxidizers for volatile organic compound (VOC) destruction. Sulfur compounds in the waste gas are oxidized to SO2 and removed by a packed bed scrubber. A fraction of SO2 converts to sulfur trioxide (SO3) before entering the scrubber. SO3 further converts to sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and generates a submicron liquid mist upon quenching the gas. New ground level pollutant regulations require removal of sulfuric acid mist before exhausting the flue gas to atmosphere. A multi-pollutant solution is needed to remove both SO2 and sulfuric acid mist.

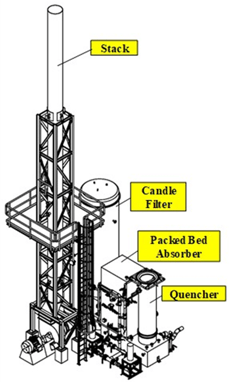

The thermal oxidizers need a wet scrubber to neutralize and remove SO2. Flue gas entering the scrubber contain some sulfur trioxide (SO3) which is converted to sulfuric acid (H2SO4) in the quencher. Sulfuric acid is a submicron liquid aerosol that passes through the downstream packed bed absorber. Some facilities are now being regulated for H2SO4. This paper evaluates and compares candle filters versus wet electrostatic precipitators (WESP’s) for H2SO4 removal in these applications.

The thermal oxidizers need a wet scrubber to neutralize and remove SO2. Flue gas entering the scrubber contain some sulfur trioxide (SO3) which is converted to sulfuric acid (H2SO4) in the quencher. Sulfuric acid is a submicron liquid aerosol that passes through the downstream packed bed absorber. Some facilities are now being regulated for H2SO4. This paper evaluates and compares candle filters versus wet electrostatic precipitators (WESP’s) for H2SO4 removal in these applications. Waste water treatment facilities operating sewage sludge incinerators (SSI) can reduce sludge volume and disposal costs by combusting dewatered sewage sludge. Emissions are regulated by the US EPA Maximum Available Control Technology (MACT) standard 40 CFR Part 60 and 62 to control particulate, lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), SO2, HCl, dioxins/furans, and mercury (Hg). Many SSI’s need a control device specifically for mercury. This paper evaluates two mercury control technologies: sulfur‐impregnated activated carbon and Gore sorbent polymer catalyst (SPC) modules. Several facilities have used sulfur-impregnated activated carbon but safety issues have arisen due to fires which have shut down some systems. The Gore SPC modules are a relatively new technology with at least seven installations. A comparison is made of capital cost, operating cost, mercury removal efficiency, fire and performance risks based on incineration of 3,000 lbs/hr of sewage sludge. Finally, an overview is provided for an Envitech SPC mercury control scrubber operating at one facility.

Waste water treatment facilities operating sewage sludge incinerators (SSI) can reduce sludge volume and disposal costs by combusting dewatered sewage sludge. Emissions are regulated by the US EPA Maximum Available Control Technology (MACT) standard 40 CFR Part 60 and 62 to control particulate, lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), SO2, HCl, dioxins/furans, and mercury (Hg). Many SSI’s need a control device specifically for mercury. This paper evaluates two mercury control technologies: sulfur‐impregnated activated carbon and Gore sorbent polymer catalyst (SPC) modules. Several facilities have used sulfur-impregnated activated carbon but safety issues have arisen due to fires which have shut down some systems. The Gore SPC modules are a relatively new technology with at least seven installations. A comparison is made of capital cost, operating cost, mercury removal efficiency, fire and performance risks based on incineration of 3,000 lbs/hr of sewage sludge. Finally, an overview is provided for an Envitech SPC mercury control scrubber operating at one facility.

Hazardous Waste Combustors (

Hazardous Waste Combustors (